Problem solving: the mathematics and the detective ways

Problem solving! It is a so popular topic that a quick Google search immediately returns 117 million results and I’m wring yet another blog post about it. On the one hand, when I’m trying to solve a problem, everything “just” works for me. In other words, I do problem solvings intuitively rather than trying to use methods (and I never want to constraint my mind that way!). On the other hand, since I do want to write a post about problem solving, I come up with the idea that I can write about the techniques I like a lot from my favorite books.

A problem well stated is a problem half-solved

Since I’m a math guy, I will start with an idea that I learned from a math book: “A problem well stated is a problem half-solved”. If I recalled correctly, I first read about it from a book of George Polya, although I now understood that it was credited to Charles Kettering. The idea is simple, yet very powerful: if you can describe your problem good enough, you already go halfway to solving it. In software development industry, I usually engage in conversation like the below:

Customer: Hi, I have a problem.

Me: Hi, what is your problem?

Customer: The application doesn’t work.

Me: Can you tell me what you mean about it not working?

Customer: It “just” doesn’t work.

Me: Are you unable to login to it? Or what feature doesn’t work as you expected? Or are you unable to access any pages at all?

Customer:

Do you find it familiar? If I am lucky, I might be able to find out what the problem actually is after 10 or 20 questions. Anyway, as you can see, I can’t help him solve the problem. A better conversation may be:

Customer: Hi, I have a problem with logging in. When I accessed the application at […] and entered my username and password to login, I got a weird error which said […]. Here is a screenshot […]

Me: Let me see. It seems the database is under high pressure at the moment…

I have seen cases in which a team discussed about how to design a feature but couldn’t reach to anywhere because the problem descriptions were obscured and every member understood it in his or her own way. Another case is when I got stuck with a problem because I was trying to think about it using customer’s words. Polya’s method suggests that:

Can you restate the problem in your own words

Restating a problem using our own words is surprisingly useful. Have you ever experienced a situation when someone is explaining to you what his problem is to ask for help, he suddenly figures out an answer himself?

A similar technique is the rubber duck method about which Coding Horror wrote a great blog post. As a side note, you probably knew that the better you describe your problem in Q&A sites like StackOverflow, the more chance it gets answered, right?

It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data.

The next four ideas come from a man who lived in England, at 221b Baker street. Yes, he primarily dealt with murder cases but I consider that is problem solving anyway. The first idea from his method is:

It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.

I can observe this type of mistakes daily.

Me: My gas hob is malfunctioning. It…

Technician (interrupted me): I knew what is wrong. It is absolutely because […]

Problem? He was wrong.

The next example happens a lot in interviews:

Interviewer: Please design a house

Interviewee: immediately draws a house

Hey man, you should ask what kind of house the interviewer wants first, should you not?

It is vital to note that by making wrong a theory about a problem, you might consequently try to twist facts and data to suit your theory. In other words, you put a boundary around your mind and wrongly eliminate all other possibilities. I got such a case recently when a colleague couldn’t login to his application locally. He spent hours to check code, database etc. In the end when I asked him to get tracing data for the login, it appeared clearly that he previously configured his machine to route requests to another application. He would have saved many hours if he had collected data in the beginning. However, I must admit that sometimes I made the same mistakes when trying to give suggestions to my teammates without knowing necessary data.

You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear

“You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear. For example, you have frequently seen the steps which lead up from the hall to this room.”

“Frequently.”

“How often?”

“Well, some hundreds of times.”

“Then how many are there?”

“How many? I don’t know.”

“Quite so! You have not observed. And yet you have seen. That is just my point. Now, I know that there are seventeen steps, because I have both seen and observed.”

What is the point of observing the doorsteps? In another conversation, Sherlock Holmes (yes, that is the name of the guy who lived at 221b Baker street) showed Dr. Watson how he could figure out his friend had bought an office with better business history than his neighbor:

Holmes: “Your neighbour is a doctor.” said he, nodding at the brass plate.

Watson: “Yes, he bought a practice as I did.”

Holmes: “An old-established one?”

Watson: “Just the same as mine. Both have been ever since the houses were built.”

Holmes: “Ah! then you got hold of the best of the two.”

Watson: “I think I did. But how do you know?”

Holmes: “By the steps, my boy. Yours are worn three inches deeper than his.

I like observing other people around me doing problem solving, e.g. analyzing tracing data or debugging a bug. Sometimes, the clues to solve their problems showed up clearly on the screens but they just didn’t notice. Looking at data is miles different from observing information/details on it.

Because I was looking for it

The dialogue below comes from a movie. I recall that there is a similar one in the books, but I wasn’t able to look it up.

Watson: How did you see that?

Holmes: Because I was looking for it.

The dialogue usually occurred when Sherlock Holmes seemed to find new clues for a case out of thin air. However, as he explained, he was able to do that because he knew what he needed to find and intentionally looked for it. This is the key. After you have necessary data and observe/analyze it, you can make educated guess about what details can help you solve your problem and try to look for it. For example, I had a case about my application sometimes consumed too much memory on a customer server. After analyzing initial data, I was able to narrow down the causes to 3rd applications installed to IIS and asked the client to collect additional necessary data for me. Knowing what you need to look for can help you find it and solve your problems much faster.

When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth

“You will not apply my precept,” he said, shaking his head. “How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth? We know that he did not come through the door, the window, or the chimney. We also know that he could not have been concealed in the room, as there is no concealment possible. When, then, did he come?”

The Sign of the Four, ch. 6 (1890)

A fun example of this idea is the multiple-choice tests. Have you ever answered a question that you know for sure A, C and D are not the correct and thus B must be the answer even though you don’t have a clue about what the heck B is. This idea is pretty straightforward, but the key point is that you must be absolutely sure that your elimination of the impossible is right. If you mistakenly eliminated the right one, you would be in a dead end.

Do not put a boundary around your mind, and forget all the methods

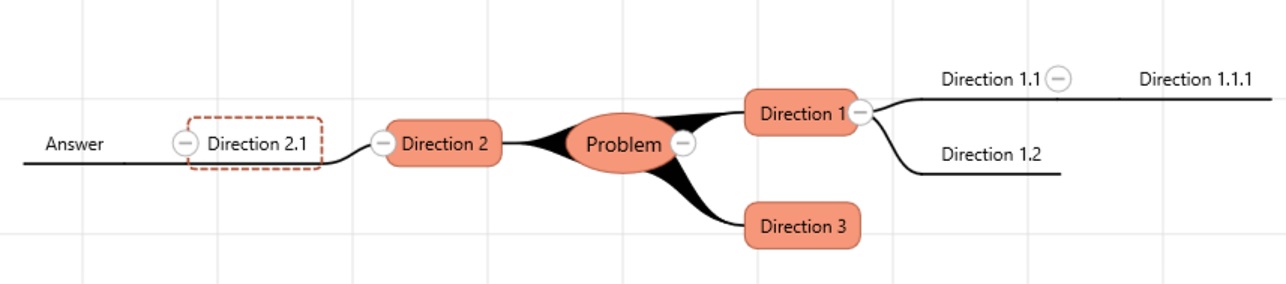

I used to take participant in a lot of mathematics exams in which I had in average an hour for a problem. While the problems were not super hard, having to solve them in limited amount of time was the real challenge. Each problem usually had many possible directions to explore, and for every further step that I explored into a direction, there were many additional directions.

When I looked back to how I did during those exams, a few key ideas stand out (note: which might make no sense to you):

- Be flexible and do not get hooked into any direction. Look at the problem from different angles and consider all possibilities.

- Forget all the problem solving methods. This might sound weird to you, and I admitted that it might be a bad advice to give to other people, but it worked for me. Indeed, I have never told anyone to do this way :P

- Trust my instinct. What directions have better prospect than the others? When should I abandon a direction and attack another one?

In short, do not stick with a single definition of the problem, do not put a boundary around your mind, be flexible, look at a problem from different angles, practice make it perfect, forget all the methods, free my mind, trust my instinct.